Of course! Why did no one think of this before? Or perhaps they did and I’ve never heard about it: it wouldn’t be the first time. I’m talking about turning books, things known for being still, into games, and in the process adding to them. Giving them new life, new energy. I’m not talking about word-books and adaptations of stories into games, because we see those all the time. I’m talking about picture-books that were already, confusingly, a kind of game.

The one I’m reminded most strongly of is Where’s Wally? That book series about finding a curly-haired, bespectacled explorer in a city of charming chaos. And you know I’ve been told I rather resemble him – I always knew he was a handsome cad! Do you remember it? Massive books with massive, double-page picture spreads, filled with the smallest, most intricate details. People everywhere, up to all sorts, every shenanigan you can think of. They might be in Ancient Egypt, a pirate town, a medieval battle: wherever the book’s creators could dream up a visually powerful theme. And you’d look at these pictures for hours, probably with friends, until you’d found every Wally (or Waldo if you’re American), every Wizard, every dog’s tail, and whatever else the book-game wanted you to find.

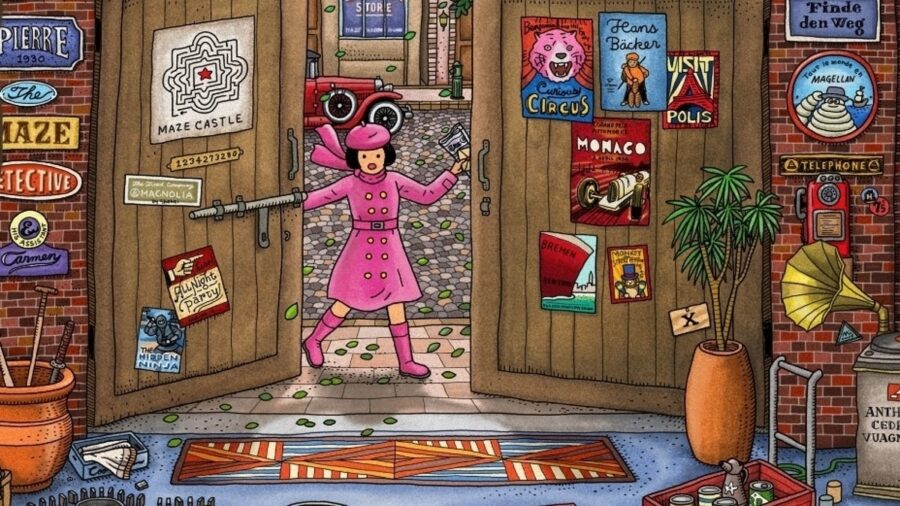

What if you turned that into a video game? What if you animated it and brought those evocative, frozen-in-time snapshots of chaos to life? Well, that’s what Labyrinth City: Pierre the Maze Detective does, and it’s an absolute delight.

This is me playing the first two levels in the game. It’s adorable!

I’d never heard of Pierre before but apparently it’s a long-running book series like Where’s Wally? The idea is slightly different, though. As you’ve probably guessed, it’s about mazes. You try to figure out a route through the hectic images to reach certain things: people, collectibles, and so on. And actually, this fundamental sense of movement lends itself better to a game because you move a character through it, rather than only your eyes.

But it’s not so much your movement that makes Labyrinth City so magical but the movement of everything around you. The scene is alive. In the opening level, a museum, statues of gods attack each other, mammoths rear up and stamp down on the floor, ninjas scale balustrades. Things move. And everywhere you look, something interesting is happening. Not a square foot is left bare. I’ve never seen a world so dense with activity. And as you walk, it interacts with you. Open windows to see tigers on the other side of them, or talk to statues, polar bears, dogs, bushes. The levels are littered with imaginative treats to discover.

And yet it still looks like the pages of a book. It’s still got a pencil-coloured appearance and wonky hand-drawn lines. Look at the screenshots in this piece: do you see? Look at that vibrancy of colour, at the irresistible charm of it all. And this seeps down into everything the game is about. It’s as enthusiastic as the two young and fearless detectives it’s about. Even the bad guy isn’t really that bad. Nowhere do you encounter anything unwholesome. And everyone uses exclamation marks! Everyone is upbeat!

That page-like flatness, with the density of the images, actually goes on to provide a rising challenge as the game progresses. It’s not always obvious where to go. Sometimes you have to go inside places you wouldn’t expect, or take paths not immediately apparent. One level flips the diagonally-down perspective to strictly side-on, which makes a bold difference, and each new level seems to introduce fresh ideas as the designers find ways to wrongfoot you.

It works. It works so well. It’s such an obviously good idea I’m almost embarrassed I assumed these experiences locked away in books forever. Why should they be? And I love it when games do this, when they find a way to rediscover something in such a compelling way you wonder why no one had done so before (I should point out Hidden Folks here, which actually has done a similar thing before, goddammit). I love it because it seems like something games are so uniquely poised to do: to breathe new life into things. And it shows why they’re so important to us, to all of us. They are the game-books of now, and more.

Eurogamer.net

Source link

Related Post:

- Labyrinth City: Pierre the Maze Detective gets new trailer

- RATCHET AND CLANK RIFT APART PS5 Walkthrough Gameplay Part 14 – PIERRE (PlayStation 5)

- Frog Detective 3 out this year • Eurogamer.net

- Game Boy Advance-style graphics combine with art in this maze game

- Pathfinder Wrath Of The Righteous Shield Maze Rune Puzzle Guide

- Hamster Maze announced for Switch, trailer

- Pathfinder Wrath Of The Righteous Shield Maze Rune Puzzle Guide

- App Army Assemble: Overboard – Is this unique spin on detective games an enjoyable experience? | Articles

- Lost Judgment investigative trailer shows off action, mini-games, and detective work

- Solve wild-western mysteries in Frog Detective 3