In many ways, Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, Marvel’s latest mega-blockbuster, is following in the footsteps of Black Panther. The 2018 installment of the MCU opened the door for Black representation in blockbuster cinema, and walked all the way to the Oscars. It took an even longer time for Marvel to get to a point where Shang-Chi could fill that role for Asian audiences.

The history of the character is far more complicated and messy than the movie’s production timeline. Originally, Shang-Chi was an extension of Marvel’s licensing deal for the problematic British literary villain Fu Manchu created by white author Sax Rohmer. Stereotypes abounded in the original Shang-Chi comic books, which had to be resolved in order for Marvel to bring this character into the 21st century. One of the people responsible for that transformation is this week’s guest on Galaxy Brains, Gene Luen Yang. Yang’s credits include the graphic novel American Born Chinese, several Avatar: The Last Airbender comics, DC’s Superman Smashes the Klan, and most recently, an ongoing Shang-Chi book for Marvel Comics.

To rethink Shang-Chi for the modern Marvel universe, Yang brought traditional Chinese mysticism and cultural heritage to the character’s backstory. For our Shang-Chi episode of Galaxy Brains, we asked the cartoonist and writer to dig into the history of Shang-Chi, his familial relationship to Fu Manchu, and how he was able to reclaim this character for Asian communities around the world. Here’s an excerpt:

What were the origins of this character and why was it not a character that was in regular rotation in the Marvel Comics universe?

Gene: I began reading Marvel Comics in the 1980s back when I was in fifth grade. I bought my very first comic from a spinner rack at my local bookstore. And back then there were some Shang-Chi comics that were around. I think his monthly series had recently ended at issue 125. So they were in back-issue bins. But as a Chinese-American kid, I was going through this thing where I just didn’t want to be Asian.

So I actively avoided picking up those Shang-Chi comics. So I didn’t know a ton about the character. I didn’t read any Shang-Chi comics until I was an adult. But from doing research in order to write the ongoing series, he began with … not-so-awesome origins. In the original run, he was the son of Fu Manchu. My understanding was that Marvel wanted to do a comic based on Kung Fu, the television series, but were unable to acquire the license. So getting the Fu Manchu license was the next best thing. And they created this character who was the son of Fu Manchu. If you read those early comics, there are really fun things about them — the way they do action is amazing. But then the character himself, Shang-Chi himself, doesn’t totally fit the Marvel mold. Like when you think of Marvel, at least when I was a kid, one of the things that I loved the most about Marvel was that the characters were meant to be relatable. Like you got to see Spider-Man go to his local laundromat to do his laundry and you identify with him. But those early Shang-Chi comics were structured that way. They weren’t structured in a way where you’re meant to identify with.

I think about Black Panther, and how it played a similar role in the MCU to what Shang-Chi is playing now, but the Black Panther comic books were very unique in that period of the Marvel Golden Age because he wasn’t a Peter Parker, a kid who’s trying to scrape by and make something of himself. This character of Black Panther is a king. You know, he’s very regal; T’Chala is not like us. He’s not relatable in that way. They found a way to make him relatable in the films, but it wasn’t quite as connected and grounded to the real world as some of the other Marvel comics. I’m interested to hear you say that about Shang-Chi, that it was similar in that it was, I wouldn’t say othering because that seems like a negative word, but it’s certainly different from how grounded the Marvel superheroes were.

Gene: Yeah, that’s right. For T’Challa, it took awhile for them to kind of Marvel-ize him, to make them fit into what makes Marvel unique. To build in those identification pieces.

I want to drill down into Fu Manchu. For those who don’t know what Fu Manchu was, or the reason why it’s offensive to a lot of Asian people, can you explain kind of what this character was and what his place in the popular culture was at that time?

Gene: Fu Manchu is what we would recognize as the prototypical Yellow Peril villain. Yellow Peril villains were a trend in the late 1800s, early 1900s of Western media portraying these Chinese characters, predominantly Chinese characters, as pretty inhuman. Like Fu Manchu was a Chinese super genius who’s bent on taking over the Western world. He had bright yellow skin, he had really exaggerated facial features, hair, pointed ears. An early Asian stereotype was that Asians had pointy ears. I have no idea where this came from! Like, I’ve never met an Asian person with remotely pointy ears. But in any case, Fu Manchu starred in these early novels written by an author named Sax Rohmer. The way I see Fu Manchu now is that I think of him as almost like a ghost. He’s not actually a ghost in the stories, but often ghost stories are a supernatural way of talking about people wrestling with their sins. The ghost in a ghost story often represents an embodiment of the repercussions of sin.

Fu Manchu became really popular towards the end. Like, I think he debuted right after what the Chinese call their “century of humiliation.” So during the 1800s, China as a nation just went through hell. They lost war after war and one of the one of the big wars that they lost was the Opium War against the British. And the Opium War was about Britain fighting for their right to sell drugs to the Chinese populace, which the Chinese government didn’t want. And they were doing that in order to even out a trade deficit. So I think deep down inside, the Brits knew that this was a bad thing. I think deep down inside the new right, they’re sinning against this other nation. In a lot of ways, the way I read Fu Manchu is that he kind of represents the repercussions of Britain’s actions towards the Chinese in the 1800s. And when Fu Manchu gets defeated in those early Fu Manchu stories, it’s sort of like the Brits writing the story about how they’re able to put off the repercussions of their own sins.

Right now you’re personally responsible for revamping the origin story of Shang-Chi. And I was wondering if you could talk us through how you approach this new story and what new details you added to the character’s backstory?

Gene: Yeah, it’s been a ton of fun to work on. I’ve gotten to work with some amazing artists. Dike Ruan and I are now doing the monthly ongoing series for the limited series that came out about a year ago. Dike did part of the art and Phillip Tan did another part. The whole thing’s being edited by Darren Shan, an amazing editor with amazing instincts. We’re all of Chinese descent and, early on, we talked about what this character meant to us. And all of us had that weird relationship that I talked about earlier, where we didn’t fully embrace Shang-Chi as kids. So ultimately, what we wanted to do was bring more Marvel into this character. We wanted to make him more of a character that we could all relate to regardless of our readers’ cultural background. We wanted them to be able to relate to Shang-Chi.

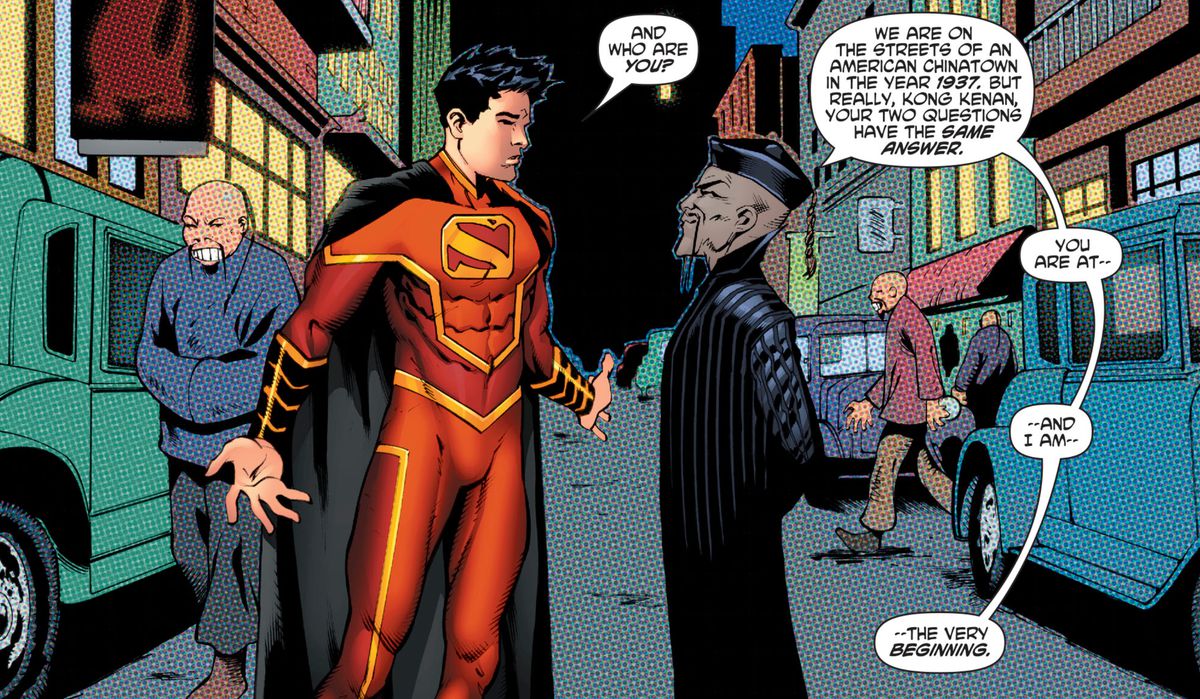

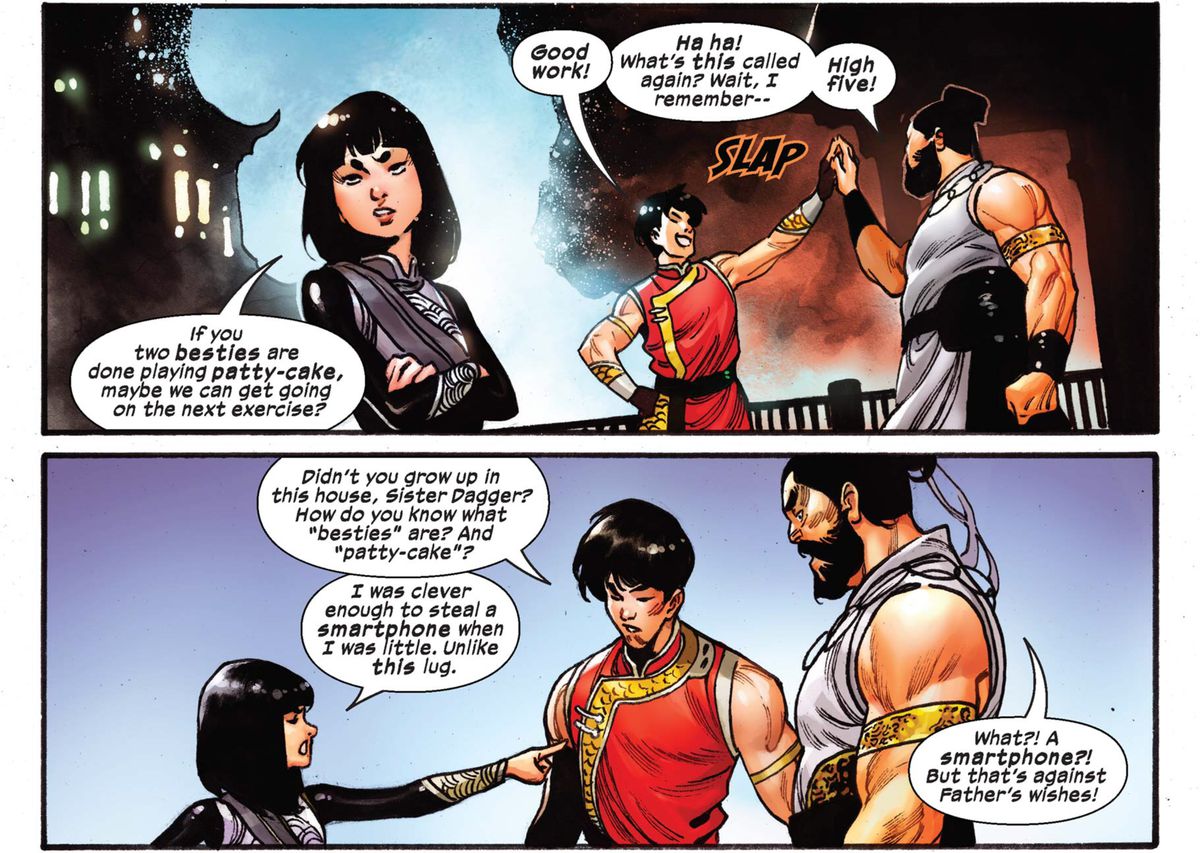

The Marvel Universe is different from DC. Like with DC, you sometimes have these hard resets of the entire universe that happened with Crisis on Infinite Earths in the ‘80s, and it’s happened again more recently with New 52. But Marvel’s never gone through something like that. Marvel’s never had a hard reset. So it means that all the stuff in the Marvel past, like the Marvel history, is still in play, which means we have to kind of figure out how to talk about all the problematic pieces of Shang-Chi without doing a hard reset. We kept the fact that Shang-Chi’s dad is a supervillain. He’s no longer Fu Manchu, but he’s the super villain. We tried to make his supervillain dad more sympathetic, but we wanted to lean into a family drama. Everybody can relate to family drama. So we wanted to lean into the tension between him and his dad, and we also wanted to give them a bunch of siblings that he could both support and squabble with.

Image: Gene Luen Yang, Dike Ruan/Marvel Comics

That family dynamic and the idea of squabbling, I think, is probably the most unifying aspect of the Marvel Universe, both on the page and on the screen. How are you going to improve upon your parents or how are you going to overcome the obstacles presented by your parents? There’s just so much that is there in these stories. Was that something that when you were reading the comics as a kid you related to or was it something that was more just like subtext that you got later on when you grew up?

Gene: Oh, yeah, absolutely. I don’t know if I would have been able to articulate it as a kid, but that was definitely something that I was drawn to. My favorite Marvel book when I was little, like when I was in elementary school, was Fantastic Four. The whole thing was about how these people love each other, but kind of hate each other sometimes, too. That’s almost all of us, the way we feel about our families. We love them. But sometimes, you know, sometimes maybe not.

There’s a big plot point in your comics about the spirit of Shang-Chi’s father and a jiangshi, which is a vampiric ghost-like creature from Chinese mythology and folklore. I’m wondering what other elements of Chinese mythology that you worked into these comics and why did you choose to tie in those specific characters, creatures and themes?

Gene: In a lot of ways, all of the work that I’ve done in comics has been about connecting with my own cultural heritage. I was born and raised in the United States, so I really only knew about Chinese culture through my parents. I remember visiting China for the very first time as an adult when I was in my 20s, and it was just weird. It was like seeing all the stuff for the first time that I had only known through echoes. So in a lot of ways my work on Shang-Chi is like trying to figure out all of this stuff. It’s kind of like a selfish reason! But I just want to figure out these parts of myself.

So one of the big pieces that we used from traditional Chinese culture is this idea from traditional Chinese medicine called the five elements. You know how there are four elements of Western culture — air, water, earth and fire — but in Chinese culture, there are five elements: fire, earth, metal, water and wood. And what we did was we had Shang-Chi come from … his family runs this organization called the Five Weapons Society, and the five weapons correlate with the five elements of traditional Chinese medicine.

So what was that experience like? Did you go to a theater? Did you try to make it an event for yourself?

Gene: Yeah, it was amazing. I went with a friend of mine who is also a cartoonist and we sat in that theater for a whole two hours … when I watched the trailer after it dropped a few months ago, I had this feeling. I don’t even know how to describe it. But basically the movie was that same feeling. For two hours, it was amazing. All the expectations that I had going in were exceeded. My friend, he’s just like the prototypical nerd, before we went into the movie was like “If this is good, I’m going to go by all the action figures.” And the first thing he did after we exited the theater was he went to GameStop and bought all the action figures..

That’s awesome. I can think back to how I felt seeing Black Panther and how a lot of people of African descent felt seeing that for the first time. And it was like, “Oh, my God, I can’t believe they made this thing.” And I had to go out and buy all the toys.

In addition to your writing, your comics writing, you are a teacher in the Bay Area and you’ve merged these two careers with an online comic book for teaching math called Factoring with Mr. Yang and Mosley the Alien. How effective do you find comic books to be is teaching tools?

Gene: I think comics are an amazing tool for education. I was a high school teacher for 17 years at a high school in Oakland, and I also got my master’s in education. So for a final master’s project,I did that online interactive comic teaching factorials, the topic from algebra.

Don’t make me remember algebra two. I’m breaking out in hives.

Gene: You’re breaking out in hives because the teacher didn’t use comics to teach you! For a really long time, the educational establishment avoided comics. There was this book that came out in the 1950s called Seduction of the Innocent that argued that comics cause juvenile delinquency. So even though that book was wrong, it had a huge cultural impact. And educators just avoided comics for decades. That’s changed recently, but in my research for my master’s program, what I found was that, out of all of the visual storytelling media — like film and television and animation — comics is the only one where it puts control over time in the hands of the reader. A comic can go as fast or slow in the reader’s mind as the reader desires. That is an incredibly effective tool. And I think that’s one of the most powerful things about comics. There’s no other visual media that allows you to do that. It’s only comics.

Dive into more Galaxy Brains with our latest episodes on Candyman, Suicide Squad, and Idiocracy, featuring future MCU star Kumail Nanjiani!

Polygon – All

Source link

Related Post:

- Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings: Who Is Shang-Chi?

- Tom Hiddleston on rethinking Loki so other actors could play him on Loki

- Marvel’s Shang-Chi Movie Gets New Trailer Showing Off Abomination

- Shang-Chi review: Marvel retcons history, delivers new magic

- 4 Marvel Films That’ll Get You Ready for Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings

- Shang-Chi’s two after-credits scenes point to Marvel’s future

- Shang-Chi trailer: Star Simu Li kicks butt in Marvel’s martial arts fantasy

- Xbox Celebrates Marvel Studios’ “Shang-Chi and The Legend of The Ten Rings”

- Shang-Chi has an Abomination fight to set Hulk villain up for more Marvel

- Is Fin Fang Foom in Marvel’s Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings?