The Marvel Cinematic Universe series Loki softens and rehabilitates its main character, playing on MCU fans’ widespread fondness for the clever, quick-witted demigod. But even though he’s a scene-stealing fan favorite, Loki isn’t a great person. He entered the MCU in 2011’s Thor as a villain and an agent of chaos, plotting to take over Asgard and dispose of his brother Thor. He’s been treated as a tyrannical Nazi who summoned aliens to destroy New York. He served genocidal overlord Thanos, and mind-controlled countless people to achieve his goals of domination. Yet a significant segment of his fanbase finds Loki excruciatingly attractive. His popularity has steadily grown over the past decade, leading to him getting his own spinoff series.

Backlash faced by fans of characters like Loki usually points out how morally wrong it is to be attracted to a self-serving, would-be tyrant. Fans, predominantly young girls or queer people, are frequently harassed online and called gross apologists when they find villains appealing. While some parts of fandom have always argued that Loki is a misunderstood, sympathetic character, other fans don’t care whether he’s ever fully redeemed. Loki works to rehabilitate him with a deep dive into his twisted psychology, which helps contextualize his actions and soften him, but the best parts of what made Loki attractive still remain. His unpredictability and ruthlessness are part of his appeal — and that’s been the case with villains for centuries.

The debate over whether it’s OK to lust after villains always presents itself as new, driven by big performative statements from people with burning attractions for, say, Thanos, or Game of Thrones’ Night King. But the argument about villain lust is as old as literature, and it hasn’t changed much over the last century. Moral purity still isn’t a prerequisite for thirst.

Villain-thirst backlash is a century old

Photo: Paramount Pictures

In 1921, matinee idol sensation Rudolph Valentino became a cause of concern to white men and therefore, mainstream culture. The source of his sudden rocket into stardom was a 1921 film called The Sheik, an adaptation of a bestselling novel. Valentino stars as the Arab character Ahmed, who kidnaps and aggressively attempts to seduce Diana, the central white female character. Eventually, his secret English heritage is revealed, and the characters run away together into the desert. In the novel, Ahmed rapes Diana, something audiences at the time would have been aware of, due to the book’s popularity. The film edges back from anything graphic, but Ahmeed leers, curls his lip, and laughs cruelly at Diana’s pain. It heavily suggests Ahmed forces himself on Diana until she falls for him.

In spite of the surprise reveal of acceptable whiteness, and the racial confusion of an Italian playing an Arabic man, Valentino was characterized as a dangerous and violent “Latin Lover.” That image of his combined allure and threat was decried as deviant, but it’s also precisely what drew fans. The sadomasochistic fantasy of The Sheik became a form of sexual liberation for women, forming a new type of masculine appeal around Valentino’s androgynous features. The resistance came from judgmental men who resented the appeal of a polished, suave foreigner.

While Valentino’s romantic-lead contemporaries were mostly white men whose characters were allowed an interiority that Valentino’s was denied, the focus on Valentino solely as a sexual object let women engage in more fantastical dreams. He was a mysterious and forbidden figure who only existed to please women, whether they relished or resisted him. The erotic cult of Valentino challenged the image of the era’s traditional male romance figure. Villains have been presented and received similarly in the century since then. They’ve never faded in popularity as sex symbols.

Rhett Butler in 1939’s Gone With the Wind was a scoundrel in the books, but a dashing leading man played by one of the most popular male actors of the 1930s, Clark Gable. Rhett is an unstable and occasionally violent man, and the lingering sense of unpredictability and danger makes him exciting and attractive. The fantasy of Rhett Butler was a safe way of exploring dangerous relationships, one where the notion of being romantically ravished was taken a little too far. As David Denby writes in his history of the film for The New Yorker, for decades the relationship between Scarlett and Rhett “has remained a subject of speculation and debate — a pop-culture obsession serving as a template for a nation’s romantic dreams and regrets.” Audiences might not yearn for such a domineering, abusive partner in real life, but there was always a certain thrill in imagining being in the hands of such an obsessive and commanding lover.

Photo: MGM

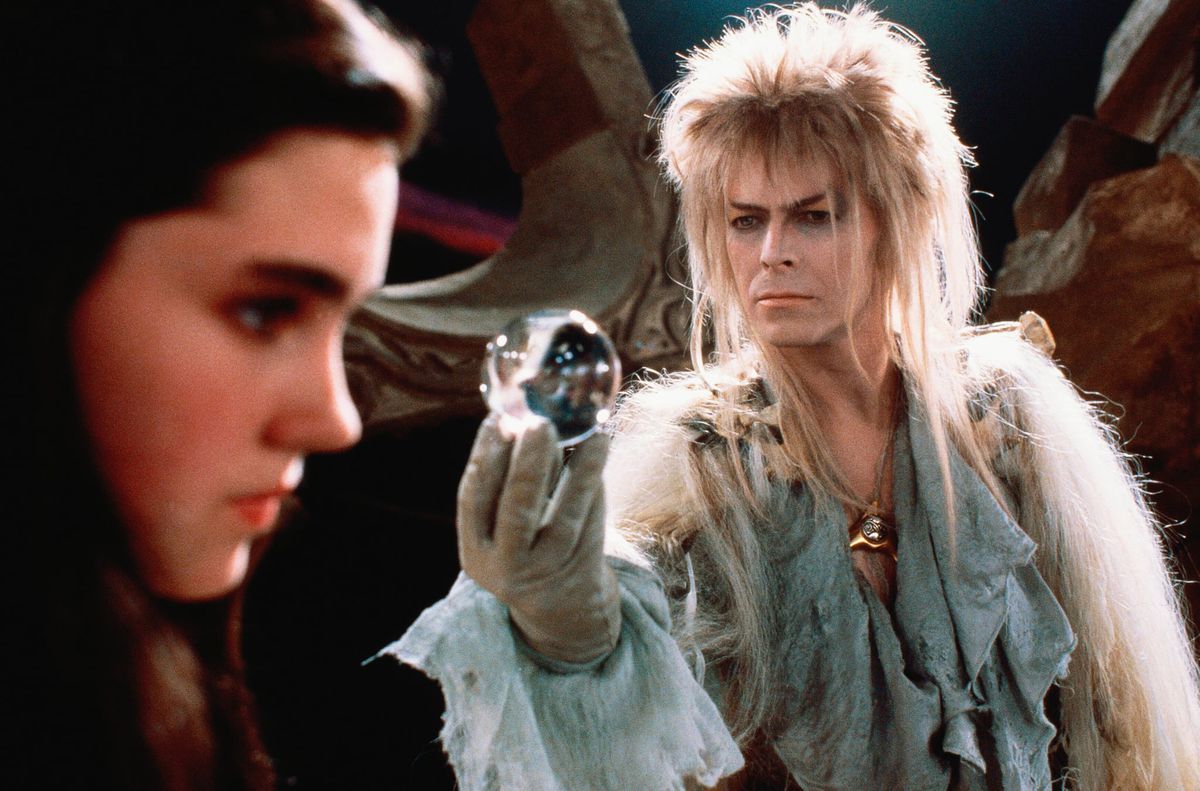

Countless villains since then have drawn attention primarily from women and queer fans, and have launched their own controversies, from the seductive Goblin King Jareth in Jim Henson’s 1986 movie Labyrinth to domineering and obsessive Edward Cullen in the Twilight books and movies. Over the past decade, fans of Kylo Ren in the latest Star Wars trilogy have inspired backlash and internet rage, and most recently, the romance between General Kirigan and Shadow and Bone’s Chosen One protagonist Alina has kicked up an online war of words.

And it all feels exactly like the culture war over The Sheik a hundred years ago.

Villain thirst is inevitable, unless…

If film and TV creators wanted fans to stop lusting after villains, they’d need to do three things:

- Stop casting attractive people

- Stop making villains suffer

- Stop writing fiction

Charismatic, attractive actors make it harder to see villains as wholly evil, no matter what they do. In New Hollywood, the European-influenced wave of film that took theaters by storm in the ’60s and ’70s, antiheroes got away with so much because they looked so good doing it. Actors often had to fight against the audience’s attraction to them in order to be convincingly vile. Antiheroes like Clyde Barrow, brought to life by Hollywood playboy of the century Warren Beatty, taught audiences that egotism, violence, and self-hatred come in every type of package. The image of Marlon Brando as Stanley Kowalski, sweaty and shirtless in his first 5 minutes on screen in 1951’s A Streetcar Named Desire, sticks in viewers’ brains and tests their resilience — and then the rest of the movie happens.

And audiences love watching their protagonists suffer. Heroes and villains alike get put through the wringer, but by necessity of “just” endings, villains hurt more, either physically or emotionally, than heroes. Characters enduring torture or other physical pain has always been a litmus test of masculinity in narratives, from noir movies to action blockbusters. But it also functions as a way to show off and sexualize the male body, and to drive empathy with a character who’s brought low and perseveres through pain.

In the last two decades or so, villains have been subjected to all sorts of personal pain as well. As the focus on origin stories grows, paired with the rise of premium serialized storytelling, the terrible beginnings of our favorite ne’er-do-wells have taken up the spotlight, to the point where their eventual crushing defeats feel much more complicated.

Photo: TriStar Pictures

Crime movies in the 1930s featured the rise and downfall of imagined or real-life gangsters who the audience could vicariously live through, with performances that exemplified how tough and remorseless the main characters are. But modern mobsters, in a melding of old-school action and the New Hollywood search for masculinity, also have wives and kids, like Tony Soprano, or complex inner lives, like The Irishman’s Frank Sheeran. The focus on villains’ emotional pain (in the past, a characteristic largely assigned to female characters) has been a huge boon to fans for characters who are already transgressing gender boundaries. The hurt that villains experience are frequently sources of fodder for fanfiction, and the depths their emotions display are designed to appeal specifically to female and queer audiences.

The supposed danger of villain-thirst

One of the biggest arguments against being thirsty for villains is the fear that the media is grooming and influencing young women to seek out abusive, harmful relationships in their real lives. The romanticizing of Harley Quinn’s relationship with Joker in David Ayer’s Suicide Squad, or Rey’s connection with Kylo Ren in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, are the kinds of stories held up as a sign that our collective morality is slipping, as if women need to be protected from themselves.

But fandom — the place where these kinds of relationships are nurtured and elaborated on in art, fiction, and online collectives — is primarily a place to share enthusiasm and to be comfortably hyperbolic about wants and desires. For many women, fandom functions as a safe space to discuss topics that are taboo or impermissible in other contexts. Fanfiction and online discourse are necessary outlets for young people to explore ideas and themes that wouldn’t be safe to carry out in real life, such as permissiveness, power, and domination. Villains, especially, have a long history of appealing specifically to women and other underrepresented groups because of the ways they unrepentantly navigate tricky, loaded social and moral boundaries.

Photo: LucasFilm

Fans are enthralled by the idea of dark, tortured souls who, like the antiheroes of that ’60s New Hollywood wave, are misunderstood in their quest for self-actualization. General Kirigan in Shadow and Bone challenging Alina to “make me your villain” holds up the fundamental truth that all villains believe they are heroes of their own story. “The intense attraction to and love of the character of the Darkling has been seen by some as troubling,” writes Alisha Grauso in ScreenRant, “with the tone from some corners of the internet coming across as downright offended that people are romanticizing such a manipulative and toxic character.”

But villains like Kirigan or Kylo Ren are headstrong, determined, and believe they have a great purpose to fulfill. As adversaries of Chosen One characters, they have the same fortitude and resourcefulness that makes them an even match for the heroes, and sometimes their only possible companion in loneliness and struggle. While turning over to the Dark Side might not be a great idea as a real life plan, it can be an irresistible avenue to explore in fiction.

So can the sense of being dominated, seduced by darkness, or even becoming prey.

King of the thirst villains

The popularity of vampires in genre fiction feels like the ultimate expression of this fantasy: While folk tales about vampires run the gamut between human and beast, modern literature has latched on tightly to the concept of the seductive monster. The rise in vampire fiction over the last several decades has been a source of frequent hand-wringing, given that vampires represent some of society’s most sexually transgressive fantasies. Some of the earliest and scariest cinematic vampires, like the eerie creature Max Schreck plays in 1922’s Nosferatu, used heavy prosthetics and monstrous imagery to instill fear in viewers. But beginning with Bela Lugosi taking over the role of Dracula in 1931, a more suave, debonair, and less dehumanized predator emphasized the idea of seduction as a form of violence, and violence as a form of seduction.

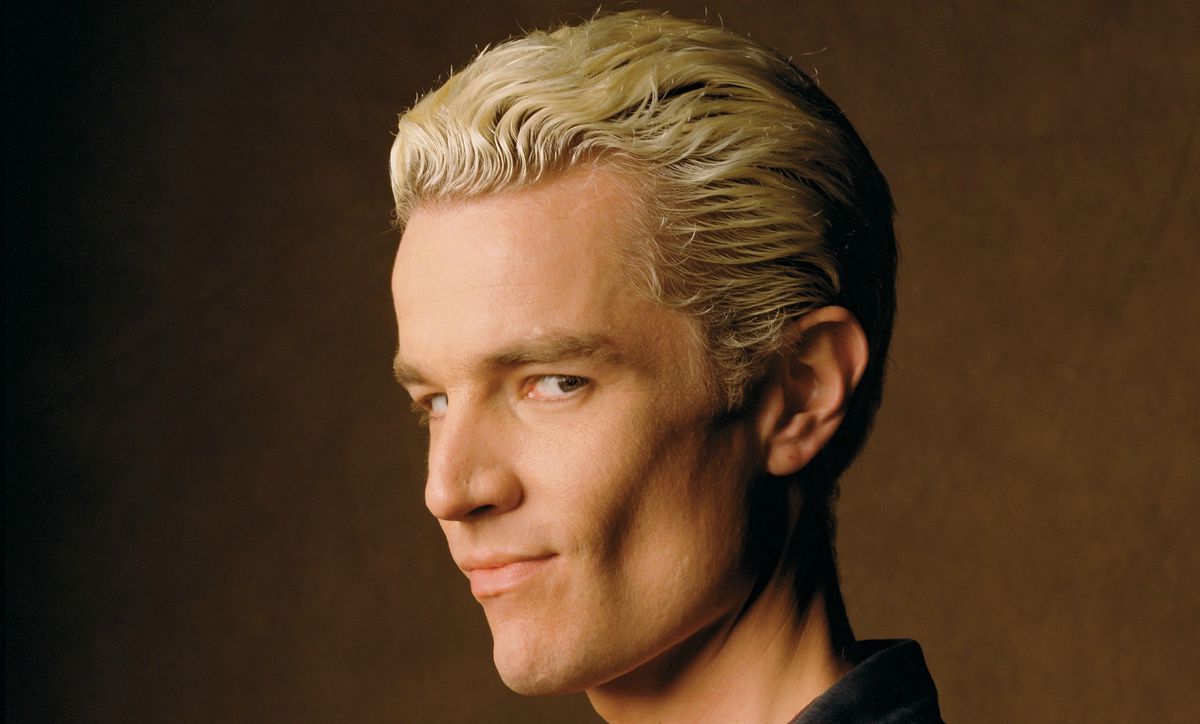

The true height of the villainous vampire as a sex object, though, came in the 1980s and 1990s. The popularity of Anne Rice’s gothic novels spawned iconic performances from Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise in the 1994 adaptation Interview with the Vampire, and influenced the public’s interest in the sexual danger of vampires on the whole. There’s a direct line between the presentation of Lestat and Louis in the 1994 film, the gradually redeemed villain Spike in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, and the presentation of romantic lead Edward Cullen and his vampire family in the Twilight books and movies.

Photo: 20th Century Fox

Spike in particular had a devoted legion of fans who were invested in his development as an antihero and eventually a full-on tragic hero, but they loved him even at the beginning, when he was breaking necks and terrorizing high-schoolers. Creators at the time responded by suggesting that female fans were hormone-addled, delusional and gullible for thinking the character could be redeemed, going so far as suggesting their hopes for Spike was similar to sending love notes to serial killers in prison.

Actor James Marsters, who portrayed Spike, reinforced this outlook in an interview with The A.V. Club. “Spike was evil, and I think a lot of people forgot about that. Joss was constantly trying to remind the audience, ‘Look, guys, I know he’s charming, but he’s evil.’ He’s a bad boyfriend. It would be bad to date a guy like this.” People who reiterate this are missing the point, though — fans of Spike’s character and arc are well aware that he’s a villain. His lack of moral compass doesn’t make him unattractive, it just makes him more appealingly unpredictable.

The next generation of vampire fiction, like the Twilight series and its many followers, argued that vampires could potentially be good boyfriends and partners. But Buffy never shied away from the predatory, demonic threat under all the glamour. Spike’s edge of danger was part of what was made him so compelling in the first few seasons.

The most-mocked fans can be fandom’s cutting edge

Women — especially young women — are consistently derided and dismissed for the celebrities and figures they find attractive, and conversely, celebrities have been derided and dismissed if they tend to draw a young, female audience. From Frank Sinatra to The Beatles to One Direction to BTS, young female fans have been targeted by pop-culture critics as the epicenter of some sort of national moral crisis, for what they love and how they love it. The modern era of media fandom has mixed in social judgment of queer people’s desires as well.

What goes ignored, however, is that these fans are often canaries in the coal mine for significant, influential works of culture. Frank Sinatra and The Beatles are two of the most important musical artists of all time, and they first came to prominence for their teen appeal before artistically “legitimizing” themselves — it’s not far-fetched to believe that BTS might eventually join their ranks.

The fandom surrounding films and villainous characters have a similar trajectory. Fans of complex and morally ambiguous characters are often a sign of a classic work in the making. The appeal of these characters signals that there’s something deeper in the work that fans latch on to. Instead of the tired moral panic about the degradation of common decency, maybe the reaction should be one of appreciation or exploration. What makes this character so fascinating? How does this fantasy serve you in a way that society won’t or can’t?

Loki does the work to get to the heart of the character, and potentially redeem him in viewers’ eyes. But more importantly, Loki goes through an incredible amount of pain to get there. The character’s emotional nuances have sustained fans for more than a decade, but he had fans from the very beginning, from the very first toothy smirk. He didn’t need to be redeemed to be loved. The tired argument that finding villains attractive is somehow a sign of moral deficiency just doesn’t hold up. It’s simply another way for society’s puritanical values to try to hold sway over the wants and desires of queer people and women. The alternative: Let people be thirsty for villains, and learn from them.

Polygon – All

Source link

Related Post:

- Who is the bad Loki of Loki? Tons of variants exist in Marvel Comics.

- Tom Hiddleston on rethinking Loki so other actors could play him on Loki

- Loki episode 3 confirms Loki’s bi — but can Marvel commit?

- Nintendo eShop leaks Avatar & Korra and Ren & Stimpy for Nickelodeon All-Star Brawl

- Vampire: The Masquerade Bloodhunt Preview – Battle Royale Meets Vampires (No, Seriously)

- Redfall is Arkane’s new multiplayer shooter with vampires

- You Can Now Own The Bike From Pokémon Red, But You’re Not Allowed To Ride It

- Developers distance themselves from publisher Tripwire after boss says he’s “proud” draconian Texas anti-abortion law allowed to stand

- New Mass Effect Legendary Edition Mod Gives The People What They Want, “Juicy” Sexy Hanar

- Crapshoot: The Russian Leisure Suit Larry with a ‘sexy’ Tetris minigame