One of my favourite things about playing games is a sensation of comfort through ‘immersion’. You hear that term a lot in discussions about games, but every player finds immersion in their own way – some delight in travelling the open worlds of places like Skyrim, others find immersion in the trickiness of Tetris, or maybe you prefer simulation style games about farming, like the wonderfully serene Stardew Valley.

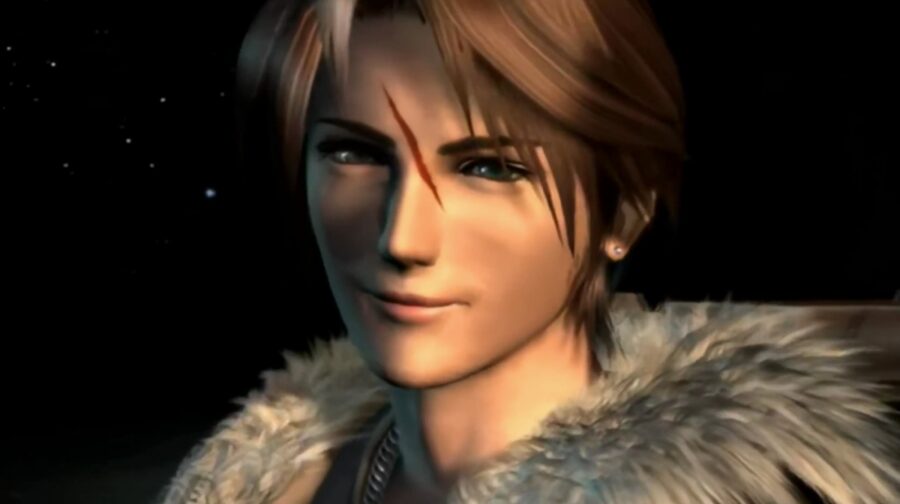

I actually find some form of immersion in all of those, but I do have a special preference: moments that are grounded and naturalistic in their depiction, usually in games that focus on story and characterisation. There is an excellent display of this concept in Final Fantasy 8, a game where you play as the protagonist Squall, a young student.

In one specific scene, Squall is sitting in a vehicle with three others just before a big mission. His posture is coiled up and tight – he stares at the floor as the vehicle trundles along, immersed in himself, you could say. Seifer, another student, sits with his legs spread out and arms comfortably draped across the back of his seat. Zell, the final student there, keeps trying to chat to Squall, his nerves clear, while the teacher, Quistis, is mainly silent, her back straight, a sense of composure about her. Because three of them say very little, you get a sense of the awkward air in the car, and we get an indication of all these characters and their personalities just from behavioural details.

In my favourite part of the scene, Zell, unable to start a conversation, suddenly gets up and starts bouncing on the spot, shadowboxing – a jab, an uppercut, and a right hook combination. He does it three times, switching his position each time. All the while the other characters say nothing, and the screen shakes slightly as the vehicle moves along. I suppose the reason why this strikes me as being so natural is that I actually find myself doing something very similar to Zell when I’m restless or bored – bouncing around, throwing out combinations. (The difference being that Zell is an actual fighter, of course, and that I would be far too embarrassed to do this outside my house.)

Seifer, growing irritated, tells Zell to stop, and the subsequent squabble is promptly shut down by Quistis. The awkward ride continues. It’s a short scene, but it manages to give you both characterisation and atmosphere and tie them together in an entertaining and natural manner – three kids who can’t get along and a teacher watching and shaking her head at their immaturity just before an exam.

Later, Squall is invited to the inauguration party for successful students – the game requires us to go to his room and change into formal uniform first, a small moment that I always find strangely enjoyable. It’s not like there is any complex mechanics behind changing – it’s simply walking into the room and pressing a button, and yet it seems to make a significant difference to how immersed I feel, maybe because it’s the preparation for going out that many of us have gone through at many times in our life. Later, we see Squall predictably standing by himself at the party, until he is dragged to the dance floor by a character named Rinoa. Fireworks go off outside, and Squall looks up at them through the transparent ceiling, suddenly unguarded, while Rinoa continues to look at him, as if trying to puzzle out what he is thinking. When she leaves, turning away, we then see Squall watching her, with an odd expression on his face – it’s possibly annoyance, but I think it’s more likely to be regret. I’m not really sure, to be honest, but either way we’ve been sucked into the emotional texture of the scene through the body language and direction, and this moment (crafted in the late nineties) is still lovely.

There are other examples I’ve come across that don’t even need to be as firmly rooted in drama to achieve a similar sensation of immersion. I’ve always been particularly fond of a moment in Final Fantasy 7 where you go to an atmospheric market, and you can visit a small restaurant with an unused stool waiting for you at the bar. You sit down, get a choice from a menu, and then wait as a chef prepares it, with a frying sound effect. Steam drifts from a pot on the hob, while the other customers sitting around you eat and another chef goes over to collect your meal from his co-worker before serving you. (Once you’re done eating you can even give him your verdict – there is an utterly ruthless ‘I’ve had better dog food’ option that I will never choose.) I think of my own experiences standing in busy restaurants, trying to keep out of the way as I wait for my order and watch the chatting customers around me.

In a short prologue for Mojiken Studio’s currently unreleased A Space For The Unbound, you wait for your friend to arrive while standing outside on a bridge. Not much happens — it’s a glimpse into the aesthetic and feel of the game, not really something that focuses on gameplay. Cars and scooters pass behind you while you lean on the bridge, and your clothes flutter in the breeze. The sky, at first a gorgeous light turquoise, slowly dims, making me wonder if rain is coming. At first I did feel a little dubious while I simply watched the screen, but after a few moments I found that the experience as a whole made me think of my own past moments where I loitered around on the streets of London, waiting for all kinds of things – a friend to arrive, a class to go to, a moment to stand in a corner and eat something, while occasionally digging into my small pockets to check my phone. This in turn helped me to connect to what was happening on the screen – it’s immersion through relatability.

None of these examples contain any actual immediate threat. They’re grounded and naturalistic in a way that captures the less frightening, jarring aspects of reality; moments of awkwardness, loitering, and dismal social interaction. I’m particularly attracted to these moments in any medium, really, whether that be books, television, films, or games, because they pull me into another place – it’s like Matilda sitting in her room, using fiction to transport herself elsewhere. It sticks with me: years after playing a game, naturalistic scenes with this approach still give me the exact same sensation of wonderful coziness.

Eurogamer.net

Source link

Related Post:

- Wings Of Ruin’s Accolades Trailer Shows High Praise

- Soapbox: In Praise Of Fire Emblem: Three Houses, Two Years On

- Games Within Games – The Best Video Games In Other Video Games

- Eurogamer News Cast E3 2024 predictions special! • Eurogamer.net

- Eurogamer Pride Week 2024 round-up • Eurogamer.net

- Who won E3? It’s the Eurogamer News Cast! • Eurogamer.net

- Three more Asterix & Obelix games due within the next five years • Eurogamer.net

- Sable might be one of the most soothing games I’ve ever played • Eurogamer.net

- Our favourite games of E3 2024 • Eurogamer.net

- Reconnecting with the way most people actually play games • Eurogamer.net