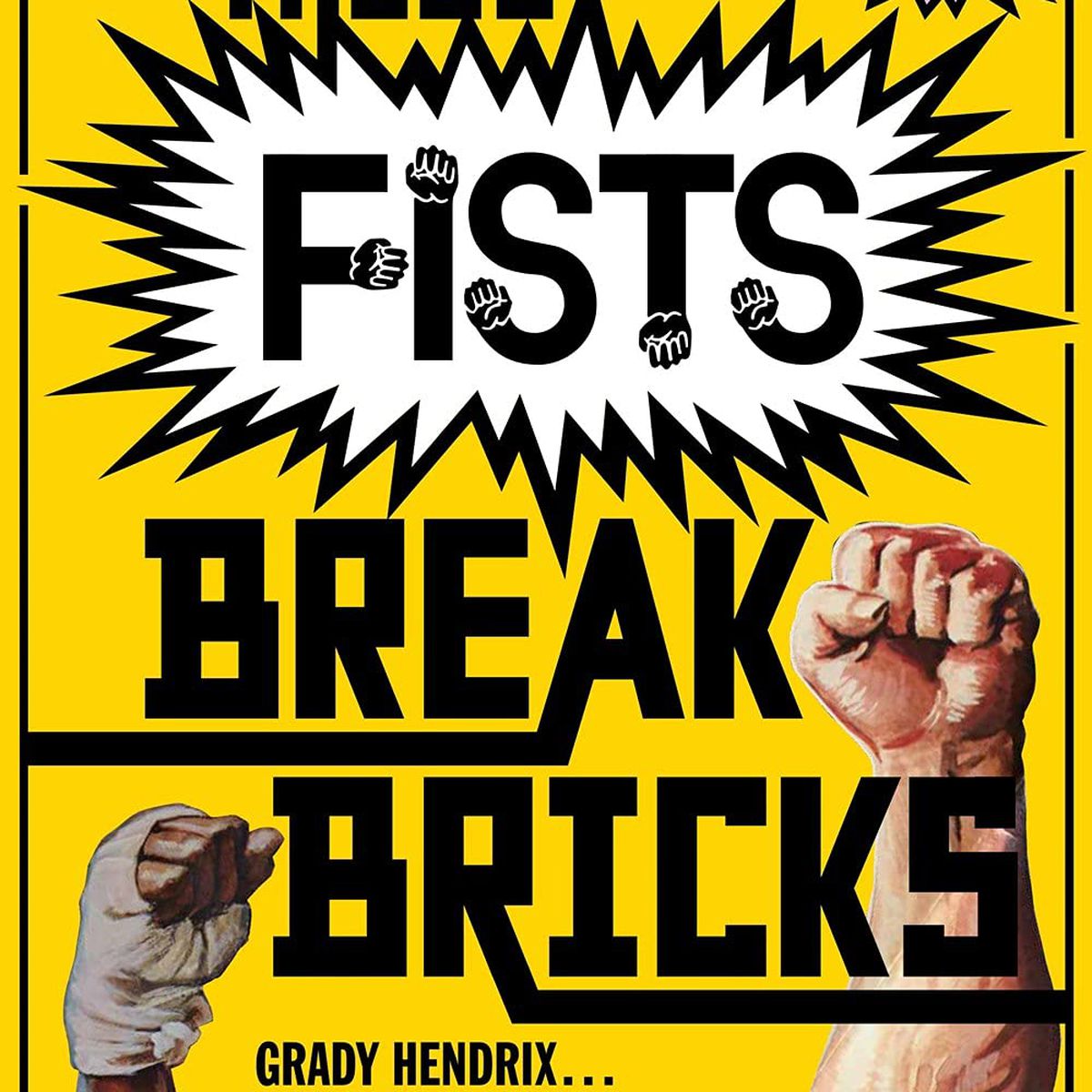

In These Fists Break Bricks: How Kung Fu Movies Swept America and Changed the World, a new book from Mondo Books, the publishing arm of the pop-culture-friendly art brand, authors Grady Hendrix and Chris Poggiali tell the story of martial arts films in America. As they say, it tells stories such as “CIA agents secretly funding karate movies, The New York Times fabricating a fear campaign about black ‘karate gangs’ out to kill white people, the history of black martial arts in America, the death of Bruce Lee and the onslaught of imitators that followed.” Ahead of its Sept. 21 release, we present an exclusive chapter from These Fists Break Bricks, telling the story of a pivotal moment in the genre’s popularity.

On a chilly night in March, 1973, the lines outside the State Theater in Times Square wrapped around the block. New York’s brand new country western station WHN had been giving out free tickets and no one did that anymore, so the crowds gathered, not knowing what to expect from this “Martial Arts Masterpiece!” that was “Stunning the Entire World.”

Exactly one year earlier, the State had hosted Henry Kissinger and Ali MacGraw at the star-studded world premiere of The Godfather. Tonight, the crowd jamming the 1100 seats were young, mostly black and Hispanic, predominantly male, and they were cynical — the first few minutes would determine whether they’d get their kicks from watching the movie or mocking the movie. The lights went down, the sleek Warners logo hit the screen, and immediately a gang of young thugs surround an old man on a dark street, mayhem on their minds. Suddenly, the 63-year-old actor leaps into the air and kicks two of the kids in the skull at once before taking the gang apart with his bare hands. No one had ever seen anything like it before. The crowd went wild.

The audience sat, riveted, even during the talky parts. Fighters tore out eyes, smashed hands into bloody hamburger, and split foreheads with iron-hard fingers, sending bright red Shaw Brothers blood ejaculating across the screen in pornographic spurts. After the hero stumbled off into the sunset in the final 15 seconds, bloody and scarred, with no one left to fight because they were all dead, the audience erupted into applause, then rushed the merch table in the lobby and stripped it bare.

Word of mouth burned through the city. People went back to see it again and again. It was the first major kung fu movie released in America and it changed the film business forever. But its star wasn’t Bruce Lee, it was Lo Lieh. And its title was Five Fingers of Death.

Directed by Chung Chang-Hwa, a Korean hired by Hong Kong’s massive Shaw Brothers studios, the movie was considered a B-list picture on their slate that didn’t even crack Hong Kong’s box office top ten, but Dick Ma, Warner Brother’s Head of Far East Distribution, picked it up because the studio had just signed a deal with a Chinese-American actor with only a single failed television show to his credit in the States, Bruce Lee, and they wanted to test the market because Warners had committed to this guy’s new movie, a disaster being shot in Hong Kong called Enter the Dragon. When their distribution manager, Leo Greenfield, got the King Boxer print into the New York office he called one of his sub-distributors, the colorful exploitation genius, Terry Levene, to come take a look.

“What do you think of it?” Greenfield asked after it ended.

“It,” Levene said, “is nothing but money.”

Warners retitled it Five Fingers of Death, opened it in Europe, where it did well, then on March 20, 1973 they previewed it in New York City. And the crowd went wild.

Images courtesy of Mondo Books

Five Fingers of Death touched a match to a powder keg. American audiences wanted movies like this, but studios weren’t delivering. Blaxploitation movies had been good business in 1971 and 1972 but faced diminishing returns. Kung fu movies offered audiences non-white heroes starring in stories about young, working class kids with nothing but their own two fists standing up to corrupt 1%-ers who paid off the cops and exploited workers. The hero would suffer their slings and arrows as long as he or she could, but finally fight back, throwing their bodies into the gears of the system, taking down as many of the bad guys as possible before they’re inevitably killed in a tornado of blood. These movies sang a primal revolutionary song: young people, kept down by the older generation, finally fight back against corruption. They spoke to young, marginalized kids who felt left behind, exploited, and ripped off. And in the ‘70s, that meant everyone who wasn’t white, and everyone who lived in a city. They were waiting for a movie like Five Fingers and they made it a hit.

The weekend it opened, Serafim Karalexis, a 29-year old Boston-based independent distributor who mostly shopped sex films, called to check on his latest flick’s New York City grosses.

“What’s going on, Howard?” he asked Howard Mahler, his local sub-distributor. “How’s business in New York?”

“Eh, it’s okay,” Howard said. “But nothing like that Chinese picture.”

“What Chinese picture?”

“Some Chinese picture that’s just doing gangbusters,” Howard said. “I can’t believe it.”

“What Chinese picture?” Karalexis repeated.

“I don’t know what the hell it is! Probably some communist bullshit!”

The next day Karalexis spoke with a European distributor who told him it wasn’t some communist bullshit, it was a kung fu movie. And it wasn’t playing Boston for another week. Impatiently waiting for it to open, Karalexis saw this unknown film’s grosses shoot through the roof. He heard rumors that every single major studio had one of these kung fu films in some stage of dubbing for release. Something big was going down.

Finally, Five Fingers of Death opened in Boston, at the Savoy. On a Sunday. No one opened a movie on a Sunday but the owners couldn’t wait. Karalexis and one of his partners got tickets for the last show of opening day. Even with no trailers, no publicity, and no ads, by 10pm that Sunday night all 1,500 seats had sold out.

“It just POPPED,” Karalexis said. “You could feel the electricity in the audience.” After it was over, Karalexis and Prentoulis went to a nearby coffee shop to talk over what they’d just experienced. Prentoulis thought the movie wasn’t very well made. Karalexis thought the movie was going to make a million dollars. It gave the audience exactly what it wanted. “We have to get one of these pictures,” he said. “If they made one, there have to be others.”

“Okay,” Prentoulis said. “But we don’t even know where they made this one.” However, Karalexis had sat through the end credits.

“Tomorrow,” he said. “I’m going to Hong Kong.”

Image courtesy of Mondo Books

He called TWA and asked for the first flight out. On Monday, April 2, at 9am in the morning he got on the plane and realized his mistake: he’d asked for the first flight to Hong Kong, not the quickest flight to Hong Kong. 34 hours, and six transfers, later he stumbled through customs and into the Hong Kong Hilton. Dazed with jet lag, he felt time running out. He’d lost a day crossing the international date line and for all he knew someone else had already released the second kung fu movie back in America. Even if he found a film and bought it, he had no time to get it dubbed or develop an ad campaign. But he’d come this far. He opened the phone book and looked up movie studios. He didn’t see any. He called the Hong Kong government and they told him to look under “cinematographers” and there he found a number for Shaw Brothers. He called and told them he was Mr. Serafim Karalexis from New York City and he wanted to buy some movies. Run Run Shaw sent his chauffeured Rolls Royce to pick him up. Then 66, Run Run Shaw turned him over to his nephew, Vee King Shaw, the same age as Karalexis.

“Put it there,” Vee King said, sticking out his hand. “How much do you pay for films?” Telling Vee King that it depended on what he had, Karalexis begged off the mandatory studio tour and went right to a screening room. He didn’t have time to watch full movies so Vee King ran trailer after trailer. After trailer. After trailer. Karalexis didn’t want swordplay movies, he wanted kung fu. And he didn’t want period costumes and historical backdrops, he wanted something modern. But Vee King saw it as a chance to dump old inventory, so Karalexis watched trailers for historical dramas and musicals, he watched everything Shaw had going back ten years, and he started to lose hope.

Suddenly, he saw it. The Duel (1971) set in 1930’s China, starring Ti Lung and David Chiang, and directed by Chang Cheh, the actors wore suits rather than robes, and used guns alongside their kung fu. Even better, it was already dubbed into English. Vee King told him Shaw had never sold a movie for less than $100,000. Karelexis got him down to $50,000 and 35% of the gross, then he packed the negative and two prints in his suitcase, called his office long distance, and told them they had a movie. Five Fingers of Death mentioned a Book of the Iron Fist so he decided to rename it Duel of the Iron Fist. While he flew back to Boston his partners found a Japanese cab driver who knew karate, dressed him in a kung fu outfit, and took pictures to use for the ads.

Without even time to submit the movie to the MPAA for a rating, Karalexis booked Duel of the Iron Fist into the first theater he could find, The Loop in Chicago, for the first date they had: Easter Sunday. It blew the doors off, grossing $12,000 in a weekend, eventually raking in over US $4 million. Karalexis’ partners told him he was a genius.

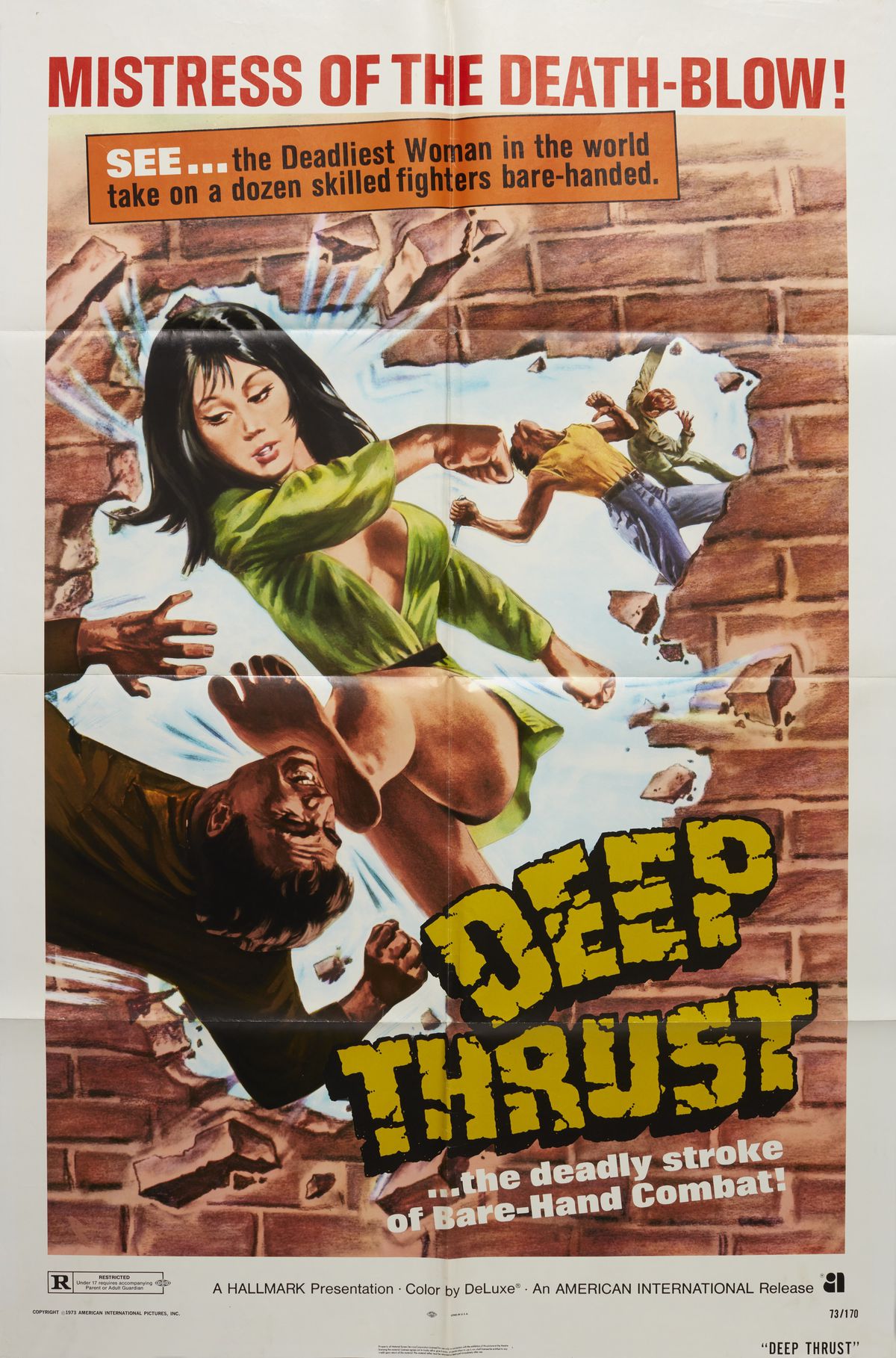

Next came Hallmark Releasing, a Boston-based outfit known for their eye-catching ad campaigns which often involved vomit bags. Their kung fu movie starred a woman, of all things, and they opened it at the Paris Theater in Pittsfield, MA. In a classy move, they called it Deep Thrust to remind audiences of last year’s hardcore porno hit, Deep Throat. To reinforce the connection, Angela Mao, its 23-year old female lead, was billed as “mistress of the death blow.” It picked up almost half a million dollars in its opening weekend.

Kung fu movies were big, but they were about to get bigger. On the promotional circuit for her new movie, Paper Moon, a reporter asked ten-year-old Tatum O’Neal to name her favorite film.

“Five Fingers of Death!” she gleefully cheered.

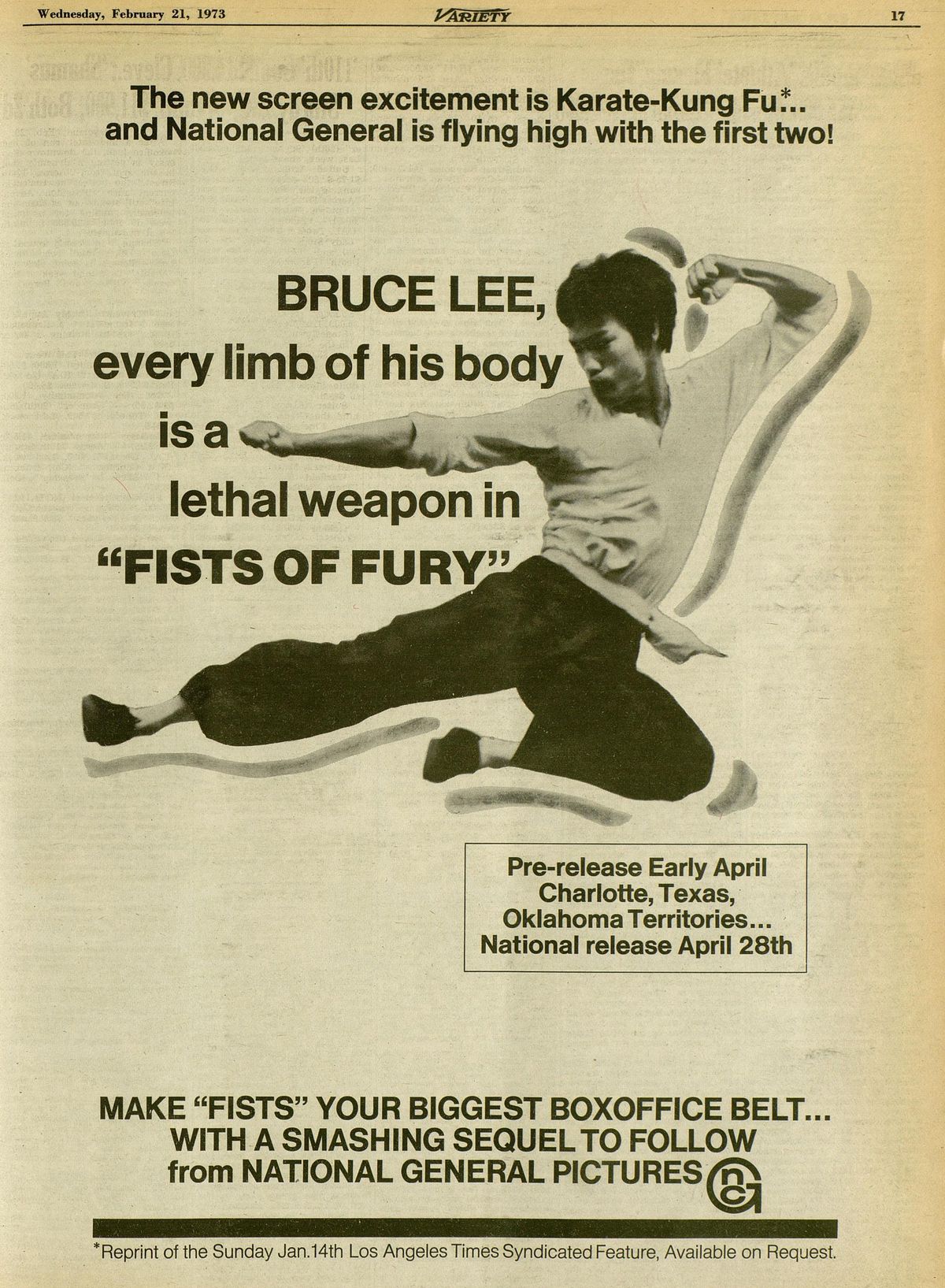

The same week Deep Thrust opened in New York City, a cheap-ass movie opened in New York City called Fists of Fury. Starring Bruce Lee it, like Deep Thrust, earned a C for “Condemned” from the Catholic church, and picked up around half a million its opening weekend. By May 16, Fists of Fury, Deep Thrust, and Five Fingers of Death held the #1, #2, and #3 positions at the country’s box office. All of a sudden, everyone wanted some kung fu. And then Bruce Lee died.

Polygon – All

Source link

Related Post:

- See What A Japanese Arcade From The 1970s Looks Like

- Marvel Future Revolution tier list and best Future Revolution starting character

- Honkai Impact 3rd Kung Fu Tea Promo Involves Fu Hua and Yae Sakura

- Kung Fu action game, Sifu, launches on PlayStation and PC in February 2024

- Top 10 best Tabletopia games to get started with | Articles

- 20 best movies on HBO Max right now (May 2024)

- 17 best movies leaving Netflix, Hulu, HBO & Amazon at end of May 2024

- 20 best Amazon Prime Video movies to watch now (June 2024)

- 11 best movies new to Netflix, Amazon, HBO Max & Hulu: June 2024

- The 25 best movies to watch on Netflix: June 2024