Wildermyth clicked for me when my greatest warrior’s human head was transformed into the head of a raven. She had just spent an evening sassing a woman cloaked in black, making fun of her mystical ways, and when that woman turned into a flock of crows the next day, my warrior’s life was never the same. She went on to slay a bunch of constructs made from cogwheels and bones by ripping at their armor with her razor-sharp beak. She entered into myth as a part-woman, part-bird, and all-powerful ass-kicking hero who bought the land a hundred years of peace.

That story wasn’t fully written by the devs of Wildermyth. There is no warrior-bird hero questline in the game. The random event that puts the player character in contact with the mystical woman who can curse you with raven-ness is one of what feels like hundreds in the game, each of which can have major impacts on your created party as they attempt to beat back a monstrous horde threatening the world they live in.

The key concept that governs all of Wildermyth is procedural generation, or, the creation of game worlds and their contents based on some broad rules. Procedural generation is also responsible for Spelunky’s levels, Enter The Gungeon’s dungeons, and the orc bosses that show up in Middle-earth: Shadow of War.

Wildermyth’s use of procedural generation is geared less toward novel enemies or giving you infinite replayable game levels. Instead, it focuses on creating the conditions where unique stories can emerge. Each game of Wildermyth is divided into three or five chapters. Some of these are more tailored to scripted plot beats by the developers, delving into a specific enemy faction and the way it must be destroyed within a long, mythic story. Others are vastly more generic, and lean almost entirely into the procedural tools. In both cases, the arc of the game is a discrete story that progresses over many years, following a rag-tag group of heroes assembled by the player.

Img: Worldwalker Games

These characters have a few key qualities. The first is their class: warrior, hunter, or mystic. A warrior fights on the frontlines, the hunter fights from a distance or sneaks behind the enemy for stealth strikes, and the mystic uses a magical capability called “infusion” to psychically inhabit environmental objects and weaponize them against enemies. Yes, in this game you can possess a bag of flour and fling it in the eyes of your enemies. It is an evocative system.

The second important thing about Wildermyth’s characters are their traits. They might be selfish, or a poet, or a goof, or a romantic, to name a few. Each character has a couple of these, and they make up the core of how they interact with the world and one another.

Each campaign largely consists of mapping the region, building useful structures and fortifications, and doing tactical battles in the small towns and villages where enemies have taken control, or defending the places where enemies are assaulting. There is a big global clock to pay attention to, which counts down the time to each enemy “invasion.” These counterattacks happen regularly enough that you have to balance the tasks you are planning to do with the necessary responses to enemy action. It’s less robust than, say, the “strategic layer” of an XCOM game, but still something that gets the brain wheels turning when you’re planning out your party’s next few actions.

Img: Worldwalker Games

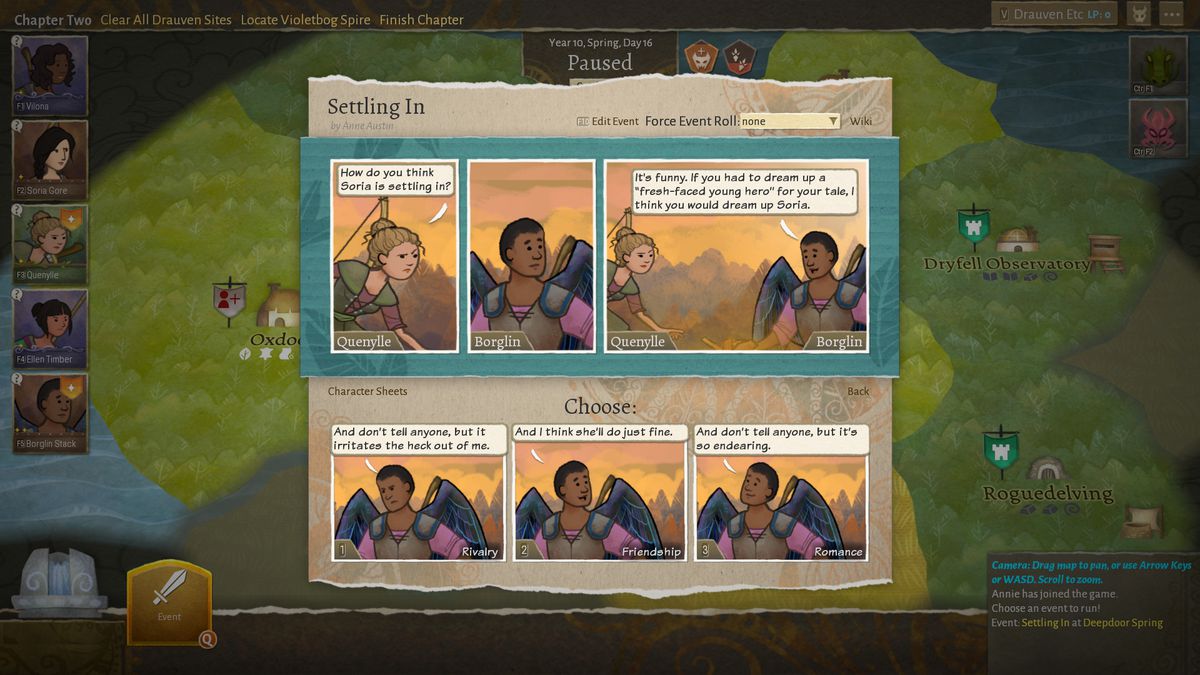

For me, the real alluring part of Wildermyth is not these (fine) strategic elements or the (very solid) tactical battles. It is the way that character traits interact with prewritten narrative chunks to create delightfully complex characters and scenarios. Before each battle, and often after, the party enters into an event structure that is pulled from a huge corpus of available story pieces. These might involve finding a riddle-locked box, getting lost in a cave, or being adopted by a fire chicken in the middle of a forest. These little stories play out depending on the characters you have and the way they approach the world. A greedy character might get distracted by a gem that, unluckily, explodes and embeds itself into their head, making them gem-touched. Another character might track down a mystical bear that murdered their mentor, and in murdering that bear they become marked with its traits.

These stories mean that playing Wildermyth is not just about doing tactical battles from one end of a scripted narrative to another. It means tracking a small crew of changing people through their careers as adventurers. Sometimes their personalities clash and they become rivals who have to one up each other; sometimes they fall in love and become an adventuring couple. All of these systems lean into one another, creating contexts and stories that follow through an entire tale of saving the world.

In a recent session, I had a rival pair, and one of them was slain by the final boss in the last turns of the entire game. I was presented with an option to either allow them to slink off the battlefield with a career-altering wound or have them strike out with their dying strength, dealing massive damage and sealing the victory. I weighed my options and had them take out the boss. What better way to end a rivalry than by saving the world?

Some of that was explicitly told to me by the game. My two characters randomly became rivals, more than likely due to opposing traits. My choice to end that rivalry in the most maximal way? That was all my own play based on the information that the game was giving me. That’s the space that Wildermyth exists within, this beautiful zone of authored story pieces and the player’s ability to string them all together into a coherent adventure. By giving us these highlights with plenty of gaps for our own invention in the middle, Wildermyth avoids the temptation to either turn this into a straight-RPG plot or the absolute freedom of a traditional roguelike, where almost all of the narrative development exists in post-game narration by the player.

The particular tone of the writing is also special here, as the stories aren’t your average fantasy fare. They are rarely about heroic exploits, and instead tend toward explorations of how these heroes are thinking about their world. They might have a discussion about whether or not destiny is written in the stars, or they might talk to a farmer about his possessed livestock and how to handle them.

Img: Worldwalker Games

These are made more impressive by the chapter structure of the game, which can sometimes put a full decade of peacetime between missions. Characters age and retire. They have children who might join you. They invest in blacksmith shops and become forest protectors. Then they’re called to action again, grab their equipment, and save the world. In one multi-part set of events, a character discovered an earth elemental, raised it for 30 years, and finally let it go live with a gargantuan forest being that, seemingly, believed it was the last of its kind. These are big stories, but they’re parceled out in such small packages that it’s sometimes surprising how hard they can hit.

I don’t have a problem becoming too attached to my characters, and I like when they die appropriately or heroically, but the game also has a “legacy” system for keeping particularly interesting people around. These allow you to save retired heroes and recruit them into future campaigns. While their narrative “progress” does not carry over, it does create very interesting scenarios where your best heroes from many different alternate universes can pal around together. Sometimes you have to choose favorites when it comes to equipment selection. God forbid.

Wildermyth hits the video game sweet spot for me. It’s light enough that I can pick it up for an hour at a time but rewarding enough that I’m always excited to see what my poetic or stubborn weirdos are up to. I’m already eagerly awaiting an expansion or new big content update, and that’s a feeling that I have not had about a video game in a very long time. I want more of this world, and more events that allow my characters to develop and change. I’ve played a lot of games that lean on proc gen in different ways, and I can confidently say that there’s nothing quite like it, and my ideal game is just more Wildermyth in every way.

Wildermyth was released on June 15 on Linux, Mac, and Windows PC. The game was reviewed on PC. Vox Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. You can find additional information about Polygon’s ethics policy here.

Polygon – All

Source link

Related Post:

- Wildermyth review – a proper RPG marvel • Eurogamer.net

- Wildermyth Review – Tales And Tactics

- I’ve never played a racing game quite like Rims • Eurogamer.net

- Soapbox: Is The Best Harry Potter Game On Game Boy Color? Quite Possibly

- Soapbox: Space Jam 2 Is A Video Game Cash-In That Doesn’t Quite Get It Right

- SMT V Inugami Is Quite the Hellhound

- Back 4 Blood Doesn’t Quite Capture Left 4 Dead’s Magic

- Suda51 Director’s Cut No More Heroes 3 Launch Trailer Is Quite a Bit Crazier

- Bungie interview: Destiny 2’s weapon crafting won’t be like other MMOs’

- Looks like Yakuza: Like a Dragon is coming to Xbox Game Pass soon